Hot Dosto Summer

The Brothers Karamazov, or tossing off the shackles of a "reading goal" in favour of the longest book on your shelf

Throughout 2021, Toronto was under some of the strictest COVID precautions in the world. Retail and restaurants were closed for most of the year. Relatedly, it was also the first and only time I read 100 books in a single year. Every year since I’ve read less than that.

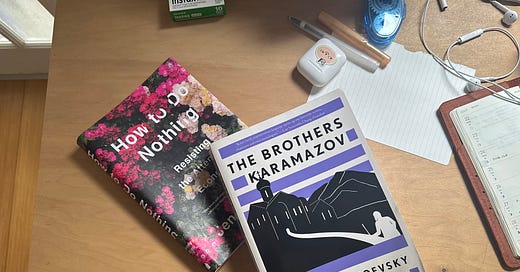

Two books that emerged from all that lockdown reading were Jenny Odell’s somewhat definitive writing on the attention economy. In both How to Do Nothing and Saving Time she unpacks how our attention and time have been sliced into economic units. From the former:

In a situation where every waking moment has become the time in which we make our living, and when we submit even our leisure for numerical evaluation […] time becomes an economic resource that we can no longer justify spending on “nothing.” It provides no return on investment; it is simply too expensive.

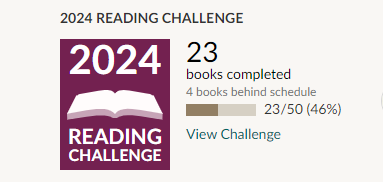

Capitalism ties productivity to morality, and productivity means the continuous production of ever more results. Reading should (and could be!) fall outside this, in the leisure realm that Odell writes about as falling at an intersection, perpendicular to the linear, productive measuring of time. But, as it so often does: capitalism intrudes. You submit your “Reading Challenge” goal to Goodreads and it spends the rest of the year telling you how you’re measuring up.

The obvious answer is to log off Goodreads, a hellsite owned by Amazon that once recommended “The Weaver’s Book of 8-Shaft Patterns” because I’d read Lauren Oyler’s Fake Accounts. Or at least, not bother with the reading challenge at all. I have done both in the past. But even without this specific technological overlord measuring an activity meant for pleasure, capitalism still casts its shadow over everything.

People avoid long books for many reasons. For myself, a genuine — and genuinely embarrassing — reason is the unshakeable feeling that reading something long “takes away” reading time that I could spend reading something else. A thought process that makes reading a series of accomplishments, rather than an act of itself.

One of the answers that Jenny Odell proposes to get out from under the long shadow of capitalism, however briefly, is to reclaim your attention by doing “nothing.” That is committing to active but slower attention. Odell mostly finds this transcendence through birding and close attention to local ecology.

This is a long-winded way to say: reading Dostoevsky is actually a radical, anti-capitalist act. I spent a lot of my “reading time” during June and July reading The Brothers Karamazov, partially because I wanted to, partially motivated by friends reading it, and also to forcibly remind myself that reading long books is worth the investment. I could accumulate a bunch of new books under my belt, or I could spend a lot of time with what Dostoevsky has to say about three brothers, their very bad father, and morality.

Let’s talk Dostoevsky

The Brothers Karamazov is 890 pages in the Michael R Katz translation I read, and 37 hours in the Constance Garnett audiobook translation (I love to duel-wield a long book). I made a meme to summarize those 900-odd pages:

Another summary could be, what if atheism killed your dad???

The Brothers Karamazov1 is about three brothers: the eldest, an impulsive rake, the middle, our passive intellectual, and the youngest, saintly Alyosha, the go-between. Their genre-definingly bad father has denied them any form of fatherly attention, as well as more practical alienations: spending their inheritances, insulting them repeatedly, and also trying to seduce one of their girlfriends. Through a complicated series of events, coincidences, and philosophical arguments, he winds up dead.

This pithy description sums up about a fraction of the experience of reading this lengthy book. The plot structure is loose, framed by a narrator who occasionally adds local opinions but is a storytelling device, not a character. Several times, just as the plot appears to be picking up, we’re sent down the rabbit hole of Christian morality.

In chasing down the transformative experience of reading something lengthy, I found myself deep in the mines of a theology based on the primacy of thoughts. That is, the Christian idea that sinning in your heart is the same as sinning.

The youngest brother’s love interest, Liza, dramatically slams her finger in a door for the vileness of her thoughts. Later in the book, tortured by the consequences of someone bringing his philosophy into action,2 the middle brother Ivan has a hallucination of the devil and tells the devil: “You’re an incarnation of myself, but only one side of me… my thoughts and feelings, but the most vile and stupid of them.”

All of this is brought to life by Dostoevsky’s gift for complexities - even the moral philosophy we can assume most closely aligns with his own beliefs is challenged by his characters and by the ambiguity of the novel’s ending. The reading process was unique, like reading a book at war with itself, playing devil’s advocate with itself. I found myself flipping back and forth between contrasting passages to appreciate how the novel’s philosophy transforms from theory to dramatic action.

How to Do Nothing argues that “leaving behind the coordinates of what we habitually notice … allows us to transcend the self,” to move beyond seeing things and people just as “the products of their functions and instead sit with the unfathomable fact of their existence.”

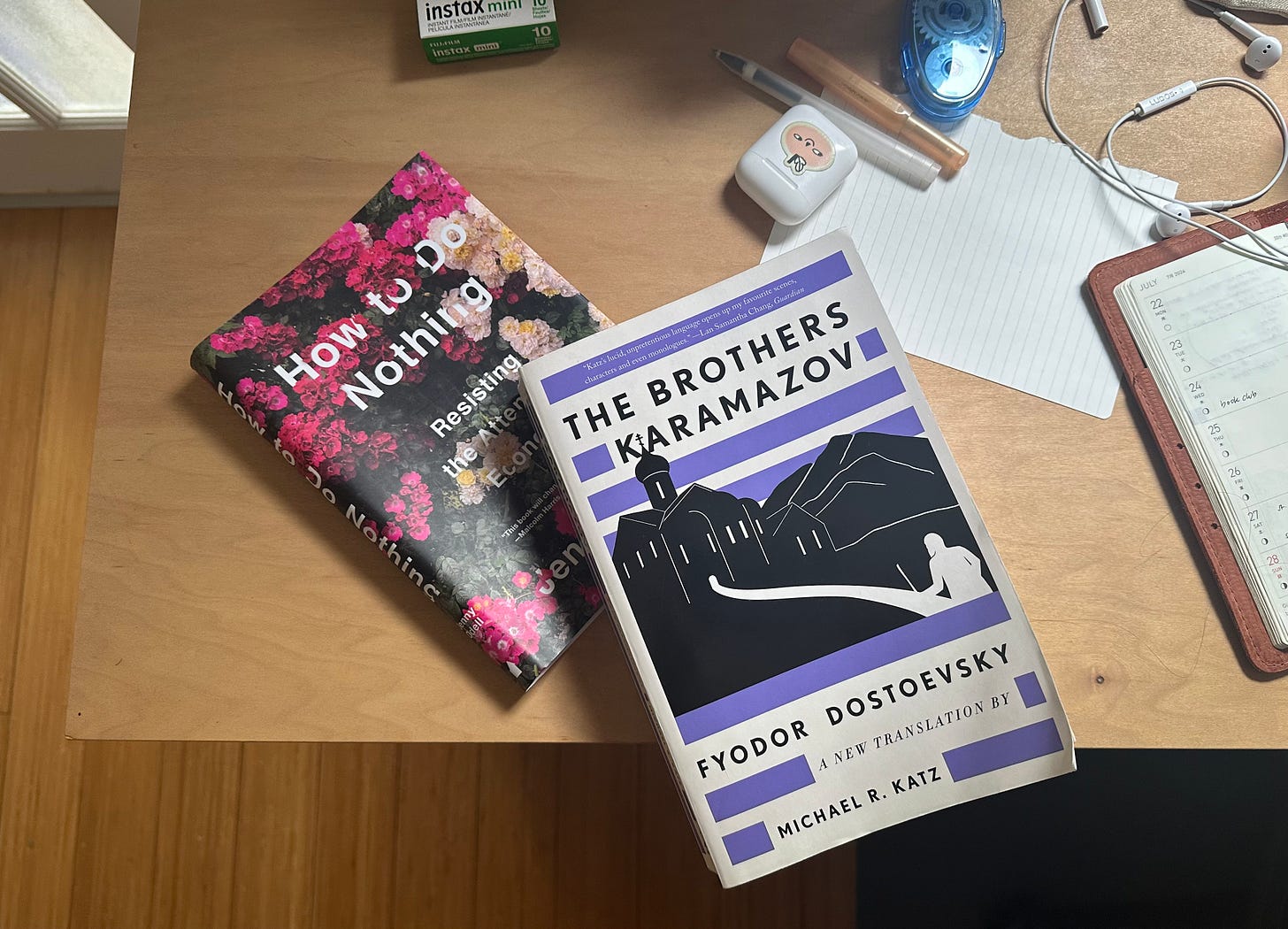

Reading a long book is its own unique attention exercise. As alluded to above, I interchanged reading it with listening to sections of the audiobook. I consumed this book on a train, in at least three cities, in the sunniest part of my backyard, on my commute to work, among other places and times. It was a real Dostoevsky summer.

In engaging with a book that goes beyond 500+ pages, you’re eventually sitting with the unfathomable fact of its existence. Nothing could matter less to the experience of reading a book like this than the addition of one more book to a roster of books read in a calendar year.

Here’s a funny question. Did I enjoy The Brothers Karamazov? Cumulatively: yes. Page by page, often no. I’m extremely glad I gave it my time and gave myself the distinct experience of a book that is equally a psychological analysis, a religious argument, and a soap-operatic melodrama.

In general, I’d prefer to use this Substack and this format to talk about books I full-throatedly endorse. I do recommend The Brothers Karamazov to anyone interested in the things I’ve talked about above. In this context, what I’m truly endorsing is picking up the longest book you’ve been meaning to read and getting going with it.

Long books, ones that force your attention back to them over and over again, and genuinely engage you creatively and intellectually, are good for you.3

A Calvacade of Karamazovs

Now that that’s out of the way, here are some specific elements that I enjoyed, in no particular order:

Dmitri/Miya’s characterization and story arc; questioning the possibility if someone motivated entirely by reputation and impulse can really change

Kolya, the world’s most 14-year-old boy, the resolution between him and Ilyusha, also one of the novel’s most moving scenes — profound fatherly love!!! I wept

Telling us about Alyosha’s fear and lack of understanding of women, spending 150 pages talking about the women in the novel, and then having them appear on page for the first time by trapping Alyosha in a room with them while they war with each other — chef’s kiss!

Katya “I Can Fix Him” Ivanovna: “I wanted to conquer him with my love”

The Katz translation renders Mitya’s dream sequence (the peasants and the babe) in present tense, a very jarring and effective choice — the Garnett translation does not. Would love to hear how other versions handle this

Can I just say that I *love* when titles use a slightly more direct translation, with an off-kilter word structure, to create something more formal, something better: “The Karamazov Brothers” sounds like a circus act. Similarly: “Monkey Planet” does not have the same panache as “The Planet of the Apes”

The aforementioned question of “what if atheism killed your dad”

It was very tempting to somehow work in a mention of Sarah J Maas’ fairy smut books, which I have read and think are quite bad, but I also think are popular because they are so long

Even after reading How to Do Nothing — and even writing about it a few times here on Substack — I still find myself falling into this trap of feeling like I've failed by not meeting my reading goal. I might compensate for this by breezing through a shorter book or easier read, and I suppose I should confront my motivation for doing so. This essay was helpful in that regard.

That being said, I did pick up Hopscotch (in Spanish, no less) here in Argentina, which in and of itself is two books, or an infinite number of books, depending on your interpretation of its mutable chapter order. I've been reading it on and off for almost three months now, and realistically I won't finish it this year, but it is nice to have as a personal challenge, one that's totally independent of my reading list or any other capitalist conventions that seek to entrap me into gamifying my reading.

I've read so many of Dostoevsky's books but The Brothers Karamazov is one that I haven't gotten around to and has been on my list for what feels like forever, so this is great motivation to finally pick it up and read it!

Reading long books is so wonderful because it's so immersive, and it really makes you feel like you're reclaiming your attention from all of the million things that are trying to distract us from thinking and feeling deeply in this day and age. Last year, I read Proust's In Search of Lost Time over the course of two months, and it was so nice to just feel like I was relinquishing myself to the meditative beauty of Proust's prose. Long books are so much more of an "experience"—I really felt like I was living half my life in Proust's world during those two months.