Mystery Novels for Snobs

Otherwise known as "novels propelled by secrets withheld from the reader, gradually investigated, that this snob (me) thinks you should read"

The promise of the mystery novel is the same as a romance: reliable structure. There is a problem, tension arises during the attempts to resolve it, and then some form of answer emerges to that problem. And like most genres with such a familiar formula, many mystery novels are bad: unimaginative in their content, stilted in their storytelling, flat characters moving through a series of diversions that add nothing to the story but delay an obvious reveal. They’re mediocre novels that treat right, wrong, and justice as absolutes that are easily understood and met out. Salacious and unambiguously evil crimes solved by someone with varying degrees of charisma and style.

I’m being a hater because, for one, that’s my whole deal, and for two, I love a good mystery novel! A thriller is one of my preferred forms of distraction reading—books read for the purpose of distraction more than all the other reasons to read books.1

I recently had the pleasure of reading a very good mystery novel by one of my favourites of the genre (see below), followed immediately by a very bad one2 by a different author. The stark contrast between the two inspired this post. Go forth & be spookèd with options ranging from:

Two variations on the detective novel

Two atmospheric “Weird Girl in the Manor House” books

Two mysteries where the answer may or may not be from this world (ghost noises)

Two (sort of) straightforward mystery novels

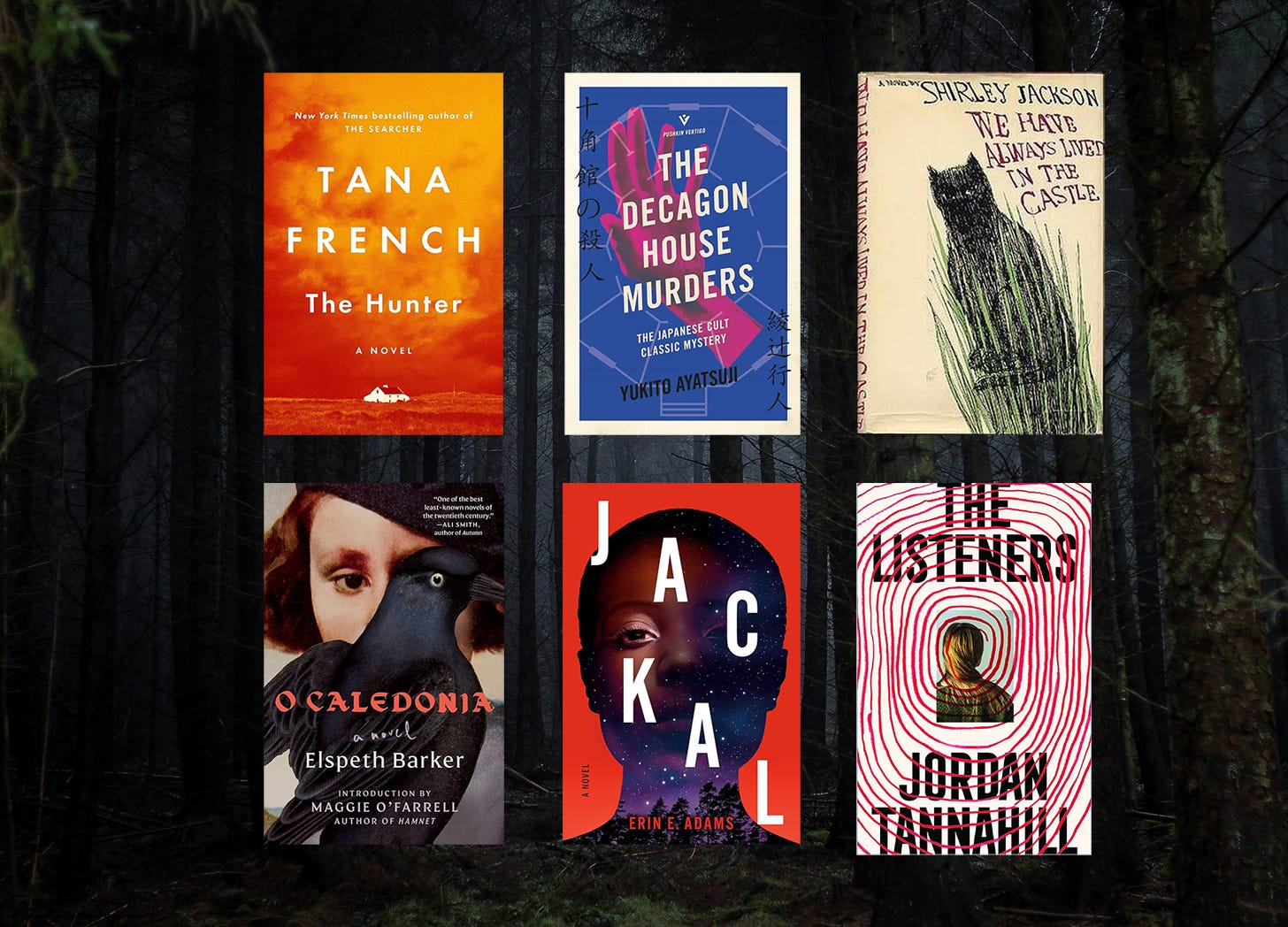

The Hunter - Tana French (2024)

Tana French is the best contemporary crime writer. Her mystery novels are atmospheric and compulsively readable. I have read all nine of her books, probably one of the only writers I can claim 100% completion on. I return to her because she is consistent enough to make it worthwhile. Her books are not “literary-fiction-as-crime-novels,” they are well just well-executed mystery novels. They feature skeptical detectives of every classification making meaty observational asides like:

Johnny Reddy has always struck Cal as a type he’s encountered before: the guy who operates by sauntering into a new place, announcing himself as whatever seems likely to come in handy, and seeing how much he can get out of that costume before it wears too thin to cover him up any longer. Cal can’t think of a good reason why he might want to come back here, the one place where he can’t announce himself as anything other than what he is.

The Hunter is her latest novel and one of her best. French excels at character and place more than inventive plots or resolutions. Despite having read all of her work, I could only give a summary of maybe one or two—except for The Likeness, which has one of the most truly bananas premises of any mystery novel. But it’s not the intricacy of her plots or the surprise of their resolutions that makes her so consistent. What puts French in another league is that she is thorough in her emotional excavation: her characters are emotionally vibrant, even when frustrating or confusing. They feel (mostly) like real people, something that is rare in a genre that relies heavily on Types.

This book picks up two years after her 2020 novel: Chicago police detective Cal Hooper has retired to the Irish countryside. He’s solved one crime there—sort of (French does not write stories where justice is easily obtained). Now he’s just trying to live a quiet life, straightening out a rough local teen and dating the charming town spinster. The story alternates between the points of view of each of these three characters, each wholly realized, with their own voice, motivations, and past.

In addition to creating stand-out characters, French is a master of place and atmosphere. The novel is set in the rolling hills of rural Ireland, as climate change burns a scorching summer into the lives of people whose futures have been sold off by indifferent politicians, people who are rich in land and history, and little else. Into this heat, our local teen’s father shows up with promises we already know he can’t keep.

It’s a slow burner, just short of 500 pages, but a Tana French novel is like settling into a familiar pattern. In her last few books, including this one, she has begun to move out of the classic crime novel form. There is no obvious crime at the outset of The Hunter, instead, just the lurking dread that something is not right. Like her other novels, I may not remember the specifics of the plot or resolution, but the atmosphere and characters linger.

Recommended for snobs who read for rhythmic storytelling, character-driven stories; also people who care about Irish history and politics. You could start here or you could start at the beginning with In the Woods, a more straightforward police procedural that (like all of her books) is laced with the wild possibility that not everything can be known and not every crime can be solved.

The Decagon House Murders - Yukito Ayatsuji (1987, trans. Ho-Ling Wong 2015)

In many ways, this is the polar opposite of Tana French. The Decagon House Murders is a puzzle-box-like pastiche that explicitly references Agatha Christie’s classic, And Then There Were None. Seven students, members of a university “mystery club” go to a remote island to solve a murder. If you’re familiar with Agatha Christie, you can imagine what happens next.

The Decagon House Murders is an example of honkaku, a Japanese revival of classic English detective novels, such as Agatha Christie, that arose during the 1980s. They are the kind of mystery novel that invite the reader to try and solve it themselves. From The Guardian:

Honkaku stories have more in common with a game of chess than some modern thrillers, which can be filled with surprise twists and sudden reveals. In honkaku, everything is transparent: no villains suddenly appear in the last chapter, no key clues are withheld until the final page. Honkaku writers were scrupulous about “playing fair”, so clues and suspects were woven through the plot, giving the reader a fair chance of solving the mystery before the detective does.

This one is a locked-room mystery within a locked-room mystery. The students come to solve an impossible crime and find themselves within another. It’s meta, but without any winking acknowledgment of that fact.

If The Hunter features rich characters who act according to impulses shaped by the world around them, this is the opposite. The characters are flat, with just enough characterization to set them apart from one another or to define them as a specific type. They’re chess pieces. I don’t want to say too much: the story is very straightforward, and the pleasure of reading it comes from watching the moves fall into place.

This is one of only two books that has ever truly, as they say, gagged me.3 I will note that I found the translation occasionally a little clunky and stilted, but this is not a book to be read for the prose.

Recommended for snobs who like puzzles and inventive homages to classic whodunits that stand on their own.

Two vibe-based mysteries ft. the most spooky thing of all: teen girls in remote houses

We Have Always Lived in the Castle - Shirley Jackson (1962)

It feels like a bit of a cheat to put Shirley Jackson on this list. Does she need more praise? There are awards in this genre named after her! But I have more to give! We Have Always Lived in the Castle is less than 200 pages and not a single sentence goes to waste. It is perfectly paced and expertly told. It’s a claustrophobic, atmospheric tour-de-force. Like any good gothic novel, it starts with a bang:

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in our family is dead.

Two sisters and their ailing uncle live in a large manor house on the edge of a New England village. They are outcasts from their small community due to the looming mystery of what happened to the rest of their family. The protagonist, Merricat, is the only one who leaves the house. All she wants is for things to stay the same. But change is inevitable. This is a taut, tense book that builds suspense right up your spine until it needs to be shaken off.

Recommended for snobs who have already read the approachable gothic classics (eg the Rebeccas and the Frankensteins of the world) and want to round out their reading with this short masterpiece.

O Caledonia - Elspeth Barker (1991)

To quote Molly Young, whose review lead me to this book, O Caledonia has “the appearance of a mystery… but not the temperament of one.” In the opening paragraph, we are presented with a dead teenage girl, “twisted and slumped in bloody, murderous death,” on a stone staircase beneath a stained-glass window and an equally dead cockatoo. Despite all that drama, what follows is not a whodunit: who or what killed Janet is not the subject of the book.

It’s instead about who she is up until that moment, and what led her there. It is a character study of a teenage girl living in a bleak, remote castle in Scotland. Chills abound, but they are mostly caused by “profound social alienation” and “bad parenting.”

The writing is beautiful and evocative: every setting, object, and experience is vividly, sometimes elaborately rendered. Originally published in 1991, the book was reissued with glowing praise from Ali Smith and Maggie O’Farrel, the latter of whom writes an introduction for the current version, as a rediscovered classic.

Recommended for snobs who have already read We Have Always Lived in the Castle; the books are thematically similar but very different in execution. Also for anyone who chooses books based on the quality of the prose.

Stephen King Alternatives

It is worth noting that I…have not read a single Stephen King novel. He’s written over 50 and I’m sure some of them are good. But I’m invoking his name as the stand-in for ‘horror-mysteries with an edge of the supernatural.’

Jackal - Erin E. Adams (2022)

There are a lot of forgettable thrillers out there. Jackal was, to me, an excellently executed version of this often pulpy genre. In this supernatural horror thriller, set in the rust belt of Appalachia, generations of young, Black girls have gone missing under mysterious circumstances in a mostly white town. We see and hear snippets of this throughout. The story kicks off with the protagonist, a young Black woman, begrudgingly returning home for a friend’s wedding. As you can imagine, she quickly finds herself in the middle of this long history.

It’s haunting for obvious reasons (it’s a horror novel, there’s gore) and less obvious ones: through i’s use of genre conventions to explore race, justice, and whose mysteries get to be solved in novels like this. The first half sets up the town, the stakes, and its history; the second half lets all of those unravel. Out of everything on this list, if you’re looking for a mystery specifically written as a page-turner with lots of intentional cliffhangers that will be resolved by the end of the book, this is a great choice.

Recommended for snobs who want a thriller with a bite (pun intended) and are okay with a little bit of supernatural.

The Listeners - Jordan Tanahill (2021)

The closest comparison I can make to sell The Listeners is to the short-lived, cult tv show The OA. If you’ve watched that, read this. Here’s what they have in common: they’re both ambiguous, strange mysteries about people from all walks of life in suburbia, the force that draws them together is unclear, it disrupts their quiet lives, and you can feel a dramatic clash coming around the corner.

In this book, a schoolteacher cannot stop hearing a low hum at all times. She slowly finds others with the same problem, including one of her students. In their relationships with one another and in their increasing isolation, the novel contends with ideas about conspiracy and social cohesion. I’d put it closer in the camp of “literary fiction” than genre/sci-fi, which is a roundabout way of saying Tanahill cares less about solving the mystery than he does about living with the ambiguity of modern life—and also, there are no quotation marks.

Recommended for snobs who want to get ahead of the game on the forthcoming four-part BBC series starring Rebecca Hall coming out this year. Jordan Tanahill is an award-winning playwright (Toronto local!) and he also wrote the screenplay, so (my) expectations are high. Also for people who mostly read literary fiction who are willing to dip their toes into this sort of sci-fi, vibes-based mystery.

Well, that’s six recommendations done and dusted. Here are the other mysteries plaguing my life:

The production of femininity in The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives. For those unfamiliar, this show follows 8 Mormon women in Utah. A swinging scandal starts the show, but it backs its way (intentionally or not) into many other topics: narcissism in the video age, Mormon capitalism; spiritual commitments to Dyson air wraps. On the last note: the inimitable sociologist and writer, Tressie McMillian Cottom, has written so much on beauty, one of those topics being that women who show visible signs of grooming, whether or not it looks good, are rewarded (specifically financially in the labour market) because it shows a willingness to conform to patriarchy, and also about what “blonde” means in America. I am truly fascinated by the hairstyling on this show: big, bouncy curls that stop being curly about 4-6” from the bottom — it’s a hairstyle and not actually curly hair! There’s an entire essay to be written analyzing the visual language of Utah and its role in gender and sexuality… Men are necessary (can’t get into Mormon heaven without one!) but the most potent relationships on the show are between women. This not a mystery I can solve. Will momtok survive this?

How to bring another pair of pants that fit into Canada without paying $35 for shipping and $40 on duties. The evergreen Canadian problem.

Is it possible to do the Artist’s Way while maintaining my usual sense of detached irony?4 Embarking on a second round with Julia Cameron’s self-help classic this October, this time with weekly group meetings!

Learning, growing, understanding the human experience, etc.

Janice Hallett’s The Mysterious Case of the Alperton Angels: A Novel. More on this during a future reading round up. Suffice it to say: skip this.

The other one is Gone Girl, which I read shortly after publication due to the more-than-glowing review from NPR’s Linda Holmes, which meant I went in completely blind and audibly gasped on an airplane during the reveal. Something (spoilers for Gone Girl!) that is not talked about enough in terms of how the book pulls of the twist is the fact that the first half of the novel is partially told in diary entries, an ingenious way to build credibility through “primary documents” with the reader. Maybe I should have included Gone Girl on this list: so many have tried and so few have succeeded.

No.

Funny, The Likeness, for all its unbelievable premise is my favorite Tana French. I found it evocative of The Women in White.

Just ordered O Caledonia based on your rec; thank you! (For anyone open to the notion: I’d recommend my debut novel as one that would fit on this list, a sort of Immigrant Gothic that Kirkus said is “gothic in tone, epic in ambition, & creepy in spades,” & genius of creepiness Carmen Maria Machado called it “an extraordinary literary and gothic novel of the highest order.” It also got me on the decennial Granta Best of Young American Novelists list. Title: The Border of Paradise.) ❤️