If you’re interested in reading Miranda July’s All Fours, I highly recommend finding a friend to read it with you. It is funny, wild, and has enough to say that you will want someone to discuss it in minute detail. Personally, I read it both as part of a book club and also alongside my housemate, Alanna.1 She sped through it in two days, and I had to stretch it out over a week: Alanna was propelled by anxiety and I was hindered by it.

For those unfamiliar: All Fours is a zeitgeisty book that will be prominently displayed on the table of your local independent bookstore the next time you go in. We follow an unnamed protagonist, who is married with a child and bears several notable similarities to July herself. She is an artist whose work covers a wide range of media: film, writing, visual art, as well as nebulous other forms.

The plot follows her ‘celebrating’ her 45th birthday with a journey of personal and artistic discovery that forces her to reexamine what she wants in sex, romance, and life in general. This is a very general description of a messy book that involves a lot of body parts and personal discovery⸺ if you’ve read the book, feel free to laugh.

Bodies

I read long sections of the book with a knot in my stomach, cringing at the absolute conviction of the decision-making. It seems especially appropriate to have such a visceral response to a book in which bodies are such a central concern. Even the title, All Fours, puts the image of a body in your mind without having to say much.

There is so, so much body in the novel — it is a book about desire (all kinds) and perimenopause. Many of the ways bodies figure into the book are intentional — some of them are a little less? In the vein of what feels less intentional: the narrator speaks about broad swaths of women her age with an assumption of body neutrality that is only afforded to thin white women. The novel reckons with the sudden changes to a body that often felt like belated revelations of someone who has never experienced external judgment on their body, its size, weight, and shape.

The only other Miranda July work I’m familiar with is the film, Me and You and Everyone We Know. Both that film and this book use bodily fluids in a similar and strikingly effective way. They use their innate shock value to break through and show something genuinely interesting, and certainly memorable, about intimacy and the desire for it. Without getting into specifics, All Fours has two notable scenes like this. In both the movie above and the book, it might be the moment you walk away remembering. The shock value of these scenes entirely blasts through the reading experience..

Self

Reading it, I kept joking that I was reading Hannah Horvath (the protagonist from HBO’s Girls) all grown up—the profound conviction of artistry, an impenetrable self, a solipsism. It’s not hard to imagine Hannah saying she has a “journeyman’s soul,” a repeated refrain in the novel.

It would be easy to fall into the trap that criticism of Girls also got:the confusion of autofiction, critiquing Dunham for Horvath and July for her unnamed character. But the novel has more self-awareness than its narrator. Over and over again, All Four’s protagonist assumes others will react to something, usually how they will perceive her. And she’s wrong half the time, in a very intentionally funny way, undercutting the character’s solipsism, her profound conviction that she has discovered something truly new.

She’s obsessed with cliffs and radical, single moments of change. Reviews from readers a little older than me spoke a lot about relatability and finally hearing ‘the quiet part’ out loud about middle age and marriage. As a reader a decade younger than the narrator, the thing I felt down in my core was all those cliffs. First, the idea that there are single, accomplishable goals that lead to immediate revelatory change:

As a girl I fantasized about the perfect dollhouse, now I fantasize about the moment when I would finally reveal what I’d been making in the garage and suddenly be seen, understood, and adored.

And second, the threat of the cliff around the corner: that everything is about to drop out from under your feet and you can see it coming, work hard enough to plan for it. None of these cliffs, in real life and the novel, are as steep as you imagine.

You don’t need to relate to, or even like the characters in novels to enjoy them. Sometimes it’s better if you don’t. One of the strengths of All Fours is that even if you find yourself at odds with the main character, it is a novel about something. Many of the novels you could lump into ‘disaster women’ stories only tentatively gesture toward what it means to be alive, politically and emotionally, in the world as we know it. Miranda July is not trying to get at universality⸺she modeled a character after herself! But it is a novel with a very loud message. It’s practically shouting at you to imagine what life could be like if you spent a little more time looking toward the horizon for possibility.

Others

There’s so much more to discuss in this book — what it has to say about monogamy, queerness, and motherhood, the false promise of relatability. There is money in All Fours (in fact, a specific amount spent memorably), but the novel is haunted by an absence of real financial concerns.

It’s a great book club book. It’s told in the first person with a casual, conversational tone full of pointed observations about life. The plot hurtles forward on a series of frenzied libidinal larks, grounded by the demands of motherhood, the echoes of a traumatic birth experience, and the long-lasting scars of generational mental health. It all works together to make something that was, quite simply, enjoyable to read.

Reading is a solitary act, beloved by loners. And yet, one of the greatest pleasures of reading anything is to pick it apart, see how it ticks and why it works. If you love something, you want to see how it works, right? This is a particularly good book to take apart with others.

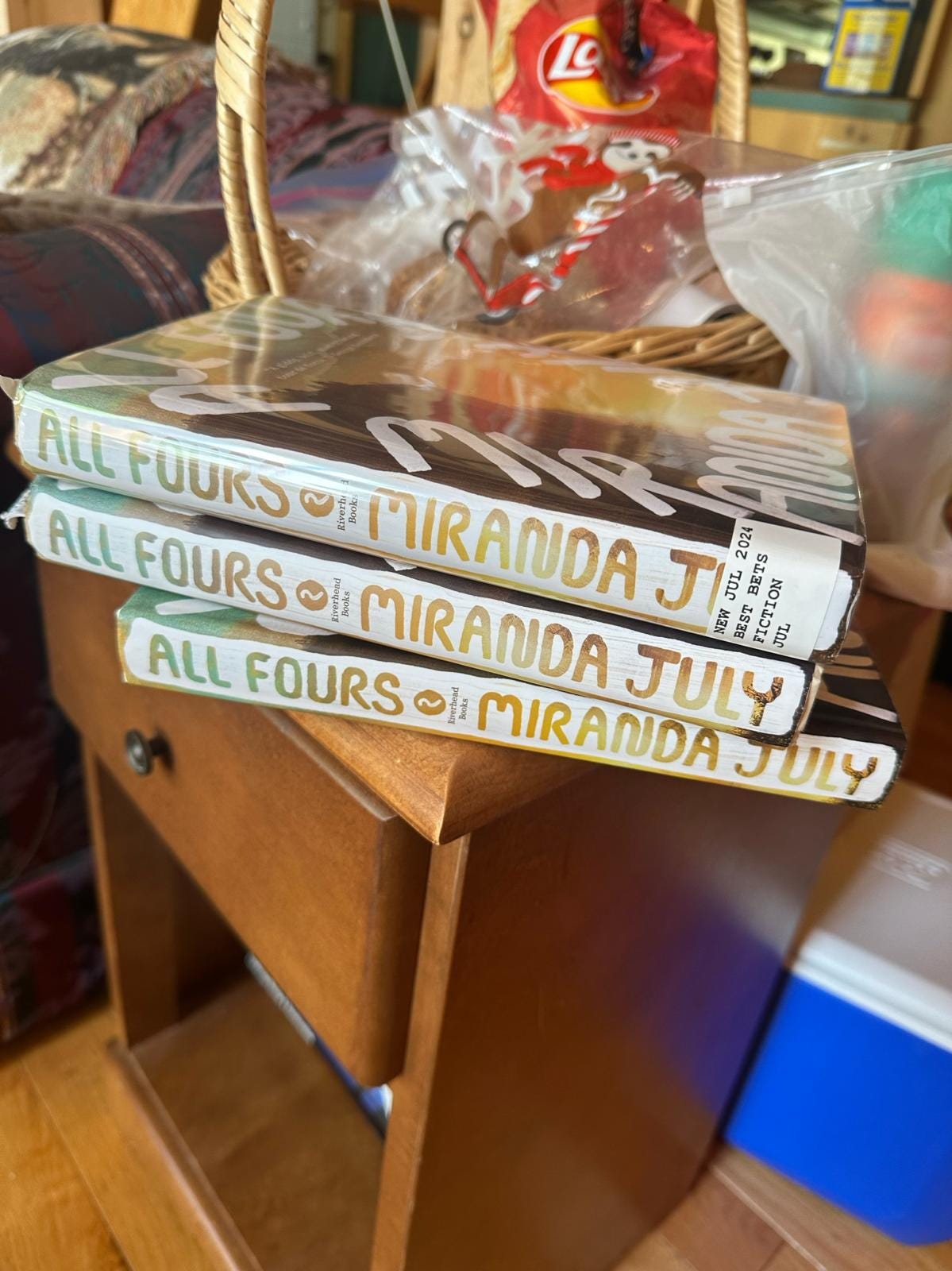

Just this weekend, a friend sent this photo from her cottage weekend. I’d recommended it to her, and then three women on her girl’s trip were already reading it for another book club. Apparently, it has started a whisper network of middle-aged women readers. From my limited view, one of the reasons the book has landed so well is in part because millennial women can see 40 around the corner, if they’re not already there. For the largest generational cohort, the ingenue years are over—Hannah Horvath would be in her late 30s now.

It’s certainly not the first book trying to unpack and lay out the demands of marriage, monogamy, and motherhood. But it has that extra layer of shareability, the moments of ‘can you believe’ and ‘oh I so relate.’ The story’s essential question is the central tension of being alive (whether or not you’re invested in marriage, monogamy, and motherhood) for a fourth decade: the opposing poles of novelty and stability. You can have some of both, but not all of either. Someone trying to find an answer to that is going to draw a lot of spectators. Bring a friend along for the show.

Housemate is the most accurate term but for clarity: Alanna, myself, my husband, and another friend all own a house together. We manage the house, eat dinner, and watch TV in some combination most days. This distinction feels relevant to specify when talking about All Fours, a novel about the vast possibilities of love and living arrangements.

yes!! i’m fascinated but not surprised that it’s such a phenomenon (i have some reservations, clearly) but it’s very easy and fun to talk about, there are many angles to take. DMs open if you do pick it up!!

I loved this! Really well done and interesting review - perhaps the only one so far that has actually made me consider picking up the book! If I do, I’ll be sure to be in your DMs about it xx